It started with big bands. Stan Kenton. Woody Herman. The West Coast Latin band Azteca. His first decade in New York City, the Horace Silver decade, included recordings with the Lee Konitz Nonet, the Gerry Mulligan Orchestra, the Bronx Latin band of Bobby Vince Paunetto, stints with the George Gruntz Concert Jazz Band, the New York Band of George Russell, Mel Lewis’s Village Vanguard Orchestra. Preceding Gruntz, Russell, and Lewis, beginning in 1978, he co-led the Sam Jones-Tom Harrell Big Band — a formative experience in arranging that was never captured on records. The 80s was the decade of the classic quintets with Phil Woods and George Robert, small ensembles that were nevertheless workshops for composing and arranging. By the end of that decade and throughout the 90s there was the miscellanea of, for example, Charlie Haden and Carla Bley’s Liberation Music Orchestra, Joe Roccisano’s big band, the South American Latin of Fernando Tarrés’s Arida Conta Group, and the tribute orchestras celebrating the music of Woody Herman and Bill Evans.

Looking back on this history you can feel the slow brew. The welling up deep down in Harrell’s musical marrow. The inner need to try his own hand at leading a big band or at least a big band session. This takes money, and he finally got that opportunity with RCA. Time’s Mirror, produced by writer, arranger, and bandleader Bob Belden, is an exercise in pure, traditional big band arranging. There is a (large) brass section, a (large) woodwind section, plus piano, bass, and drums. No “color” percussion, strings, electronica, or the like. The selection is a carefully curated and balanced set of contexts for section arranging and featured solos, with, unusually, only one Harrell original for the occasion (Daily News): the standards Autumn Leaves and Dream (Johnny Mercer), Bird’s Chasin’ The Bird for a little bebop, Harrell’s São Paulo, which was written in the late 60s but not previously recorded, for some Latin, Shapes, a Harrell composition originally recorded in post-bop funk fashion with Bob Berg (Berg’s 1978 debut album as a leader, New Birth), and two Harrell golden-oldies, Time’s Mirror for a ballad (originally recorded on the Phil Woods Gratitude album and again on Harrell’s Upswing) and Train Shuffle (also on Upswing), for some swing. In fact, speaking of a slow brew, we learn from Ken Franckling’s liner notes that most of the arrangements on the album actually go back to the 1960s.

The whole production is so calculatedly traditional that I’m tempted to say the innovation lies in its deliberate non-innovation. Of course the more musically knowledgeable will hear harmonic nuances that mark the arrangements as distinctly Harrell-esque. He indeed could have titled the album The Art of Arrangement. For me there was an additional pleasure listening to this big-band album again (I love the album and had listened to it many times in the past): hearing it pumped through a brand new receiver and set of B&W speakers, so my tweeters and woofers and subwoofer are firing on all cylinders!

Listen to the original Bob Berg combo version and then Harrell’s big band version on the opening track here, and you’ll get the idea. On the latter the full orchestra slowly, dramatically, climbs the stairs of the melody, an ascent capped by a piano line from Xavier Davis and followed by a full pause. Repeat, and pause again. Then Shapes breaks into full bore big band swing. Soloists are Alex Foster on tenor sax, Harrell on flugelhorn, Xavier Davis on piano, and Carl Allen on drums. The piece ends with a brief flugelhorn coda. Xavier Davis had been traveling with Harrell for a couple years by now, though to my knowledge this is his first time on record with Harrell. Many more were to come. The rhythm team of Kenny Davis on bass and Carl Allen on drums had been on the Art Farmer-Tom Harrell collaboration The Company I Keep, and Allen’s many recordings alongside Harrell go back to the albums they made with Don Braden and Joris Teepe. A swinging start to a big band album. (By the way, the thumbnail biographical sketch of sideman Tom Harrell on Berg’s New Birth album says “at present [he] is co-leader with bassist Sam Jones of a big band.”)

It’s funny how sometimes the arrangement rather than the melody becomes the earworm (I think for example of the famous arrangement of Love For Sale on Cannonball Adderley’s Somethin’ Else). That has happened to me here with Autumn Leaves, with the gently swinging counterpart voicing from the woodwinds that precedes the trombones playing the venerable melody. The build up to and timing of Foster’s tenor solo, the only solo on the piece, has me in Tom’s head and seeing how he is hearing everything through a big band filter. Finger snapping and visions of the dance floor. (I imagine, by the way, that Harrell will not have forgotten Don Sebesky’s arrangement of Autumn Leaves and his, Harrell’s, solo on Sebesky’s A Tribute to Bill a couple years earlier.)

Despite the titles Daily News and Time’s Mirror, there is no newspaper theme to the album, Harrell tells journalist Franckling! Daily News, the one original Harrell composition for the album, features Harrell’s flugelhorn playing off the band.

Since Johnny Mercer wrote it in 1944, many have recorded Dream, but it is best known to me from Roy Orbison’s 1963 hit, which was used in a favorite movie of mine, 1998’s You’ve Got Mail. Harrell’s “shimmering ensemble arrangement” (Franckling) is a short piece that ends in the session’s lead trumpeter Earl Gardner’s “exclamation point solo — fluttering like a bird over the final bars” (Franckling again). Gardner and Harrell had been trumpet section mates in Mel Lewis’s Jazz Orchestra and Charlie Haden’s LMO.

Hey, I know that song! That’s Chasin’ The Bird of course, sounding a little odd but having fun dressed up in big band. It is led off by Kenny Davis’s bass and solos from Davis and Harrell.

As it settles into its gently tapped out Latin rhythm, and with the ubiquity of Latin and Brazilian at the time (and still), the theme of Harrell’s São Paulo sounds to me a little like a television theme song from that bygone era. Solos by Davis, Mark Gross on alto sax, and Harrell.

In an earlier elimination round of candidates for my Horn of Pretty playlist, I had nixed Time’s Mirror as “achingly beautiful, but as such too emotive.” Nothing in this arrangement and performance makes me change my mind, at least the “achingly beautiful” part. Harrell told Franckling that especially with this number and Train Shuffle, he was trying to write more through-composed arrangements. All I can say is, sit back and listen to it.

The shuffle march Train Shuffle has always been one of my favorite Harrell songs. It always makes me smile from ear to ear, on its own musical merits and for the tradition of train songs and the role of trains in American history that it invokes. A fine swinger to cap the album, with solos from Harrell on flugelhorn, Craig Bailey on alto sax, Conrad Herwig on trombone, and Don Braden on tenor. Braden of course is a long-time intimate of Harrell’s and is also listed as a Production Consultant for the recording.

Coincidentally, Harrell’s next studio outing was, three months later, someone else’s exercise in arranging, Don Sebesky’s tribute to Duke Ellington, Joyful Noise, also for RCA. Two summers before, Harrell had participated in Sebesky’s tribute to Bill Evans, I Remember Bill. And for this one too it also doesn’t hurt that my new tweeters and woofers are fired up!

“Make a joyful noise to the Lord, all the earth; break forth into joyous song and sing praises! Sing praises to the Lord with the lyre, with the lyre and the sound of melody! With trumpets and the sound of the horn make a joyful noise before the King, the Lord!”

Psalm 98

As I wrote in my own tribute to Ellington, I’ve never cared too much for Ellington in repertory. Ellington’s music is so inextricably tied up with his immortally distinctive musicians that repertory performances just make me want to go back to the original recordings. (I distinguish repertory from memorable covers from Ella Fitzgerald, Andy Bey, Mingus, Monk, the World Saxophone Quartet and others that I’ll come back to every day of the week and twice come Sunday.)

But, as Sebesky clarifies in his love letter to the master, his intention in Joyful Noise was not to imitate the Duke. And that is immediately obvious in the tempo of the album’s opener, Mood Indigo. Let us “break forth into joyous song,” and I’m all in. Hard not to, when the “trumpets and the sound of the horn” include soloists Phil Woods, Tom Harrell (flugelhorn), Bob Brookmeyer, and Ron Carter (whose bass introduces and caps off the piece) on Creole Love Call. Among the other Ellington and Strayhorn compositions Harrell also has a muted trumpet solo on Satin Doll (a piece also kicked off and capped off by Carter’s bass; Carter also has a solo, along with Phil Woods and John Pizzarelli on vocal-guitar).

I think a special shout out is due Sebesky’s three-part Joyful Noise Suite (Gladly, Sadly, Madly), written according to the album credits under commission. It’s wonderful writing suffused with Ellington quotes and more great solos from those three amigos Woods, Harrell, and Brookmeyer (and on Sadly, another favorite of mine, pianist Jim McNeely). One of my favorite quotes is Cotton Tail, and from the Blanton-Webster era the album ends with a transcribed performance of Ko-Ko.

Milan Simich produced it for BMG, and in a short blurb he explains that As Long As You’re Living Yours: The Music of Keith Jarrett is dedicated to Jarrett’s early original music, which, he says, is perhaps in danger (1999) of being forgotten in the wake of Jarrett’s fame and accomplishments with solo improvisation and with his Standards Trio. For this tribute, thirteen Jarrett compositions were recorded at studios in New Orleans, Los Angeles, and New York by a highly diverse set of musicians playing in highly diverse styles, one of the more jazz-traditional ones being Joe Lovano and Tom Harrell. The peculiarly Jarrett-appropriate album title is taken from a song (‘Long As …) from Jarrett’s 1974 Belonging album with his “European quartet,” though the song is not one of the thirteen performed on this compilation.

In 1967-1968 I was working in a college campus record store. Charles Lloyd was quite the thing (Dream Weaver, Forest Flower). I don’t remember if I made a particular note of the quartet’s pianist, Keith Jarrett. By 1970 I was married, and as I have written before, my 1970s and 1980s were consumed by education, family, and work, and I wasn’t following music closely. I’m embarrassed to admit that sometime in the late 80s a new acquaintance who knew that I was a self-described jazz nut was flabbergasted to learn that I had never heard of Keith Jarrett’s (1975) Köln concert. My familiarity with the music of Keith Jarrett as well as Tom Harrell from those decades is only relatively recent.

And as has so often happened on this Trip, it is a Harrell record (this one) that has led me on a pleasant side excursion to explore someone else’s catalog.

To my knowledge Jarrett and Harrell have never played together, and while there is no real reason to do so, I can’t help making some comparisons. For one thing, for all practical purposes Jarrett and Harrell are the same age, so they have both lived through the same decades of evolving jazz history. Both have accumulated a prodigious recorded output, with this big difference: Harrell will play with just about anyone, Jarrett not.

And then there is Europe. Jarrett was born May 8, 1945 (thirteen months before Harrell). That happened to be Victory Day. Wolfgang Sandner keys off that coincidence in the “Overture” to his exceptionally literate biography of Jarrett, in order to make some pertinent observations about the suddenly explosive cultural significance of jazz in post-war Europe (“Pre-war Europe knew about jazz. In the days after the caesura of May 8, 1945, however, its sounds became loud enough to drown everything else out”). And because of that heightened receptivity, Jarrett ended up being equally at home on both continents, something anyone with any familiarity of Jarrett knows full well (think of Jarrett’s recordings of western classical music, think Jan Garbarek and the “European quarter,” think ECM). Tom Harrell of course has been equally popular in Europe (to Jarrett’s American and European Quartets think Harrell’s time with Phil Woods and George Robert).

Sandner is German, and the original version of his biography, published 2015, was written in German. A significantly enhanced version in 2020 was released in an English translation by Keith’s younger brother Chris Jarrett (who is a long-time resident of Germany). As a matter of fact, the one substantial biography of Jarrett prior to Sandner’s was written by an Englishman (Ian Carr). I wouldn’t be at all surprised to read one day of a biography of Harrell written by a European.

I like this compilation, especially as interlaced with the Jarrett originals, a playlist naturally I have made. The Lovano-Harrell number (with Dennis Irwin on bass and Adam Nussbaum on drums) is Shades of Jazz. This is from Jarrett’s 1976 album with the “American Quartet” (Charlie Haden, Paul Motian, Dewey Redman).

“File Under Modern Jazz”

As I have already reported, one of Harrell’s early experiences as a large ensemble player, and in particular in Latin settings, was on Bronx-born Bobby Vince Paunetto’s Paunetto’s Point (1974) and Commit to Memory (1976), which were reissued as a two-fer in 1998. There I told of Paunetto’s tragic diagnosis of multiple sclerosis in 1978, which sidelined him permanently as a vibes player, but not as a composer and arranger. In 1996 his Commit To Memory (CTM) band released Composer In Public (without Harrell), and in 1999 Paunetto produced, composed, arranged, and conducted Reconstituted for a CTM nonet, this one with CTM veteran and fellow composer and arranger Tom Harrell.

Harrell’s only solo is a nice flugelhorn one on the opening track, Silva! Horn! & Down Pat! (dedicated to fellow Cal Tjader alumni Jose “Chombo” Silva, Paul Horn, and Pat Patrick). Paunetto’s compositions are complex, especially rhythmically, and not easy to characterize, certainly not “Latin” in any stereotypical way. “File Under Modern Jazz”!

In several ways Reconstituted is a 70s family reunion. As the liner notes point out, most of Reconstituted‘s nonet are Woody Herman alumni (Harrell, Glenn and Billy Drewes on trumpet and woodwinds respectively, Mike Richmond on bass, Gary Smulyan on baritone sax, John Riley on drums, and Larry Farrell on trombone). Harrell, the Drewes brothers, and Richmond are also alumni of the 70’s CTM, along with pianist Armen Donelian and saxophonist and flutist Todd Anderson. There are also Paunetto family dedications. On Paunetto’s Point and Commit To Memory, “Bobby Vince” and his brother Ray dedicated several tracks to their late brother William (Will); on Reconstituted, Bobby dedicates My Brother The Great! to Ray, who passed in 1998. Bobby Vince, who passed away in 2010, synthesized many strands of Latin and New York City music; if you are as interested in the subject as I am, here is an excellent article.

Bernstein is a tenor, alto, and soprano sax player who was born in Brooklyn (1961), graduated from Berklee College of Music (1984), and played with, among many others, Harrell bandmates Hal Galper and Billy Hart. In the mid 90s he met two important people, fellow musician Tom Harrell and a Danish woman named Laila. He married Laila, and they made a home in the Jutland region of Denmark, where Bernstein has been both an active player and an educator on the jazz scene ever since (his pedagogical credits include co-leader of the jazz faculty at the Syddansk Musikkonservatorium in Denmark and leader of the Rhythmic Music Department at The Southern Danish Conservatory of Music).

Marc Bernstein Presents “Dear Tom Harrell” combines tapes from three separate recording dates that Danish label Storyville Records packaged into a single CD. First, Bernstein had organized a tour in Denmark playing the music from Harrell’s The Art of Rhythm, and Madrid and Recitation (tracks 5 and 6 on Bernstein’s CD) were from the tour’s inaugural live performance at the Musikkonservatorium, played with young Konservatorium musicians, including strings on Recitation. Not surprisingly the playing is a little raggedy compared to the professional level of The Art of Rhythm, but it is thoroughly enjoyable.

Five days later Bernstein and Harrell squeezed in a five-hour studio session in Copenhagen with three young up-and-coming Danes on piano, bass, and drums before Harrell had to hop a plane to Italy. Out of this came the first four tracks on the CD, my favorite of which is the drummer Morton Lund’s jaunty Off To Munich.

Finally, the last two tracks are from an “impromptu” studio session in Brooklyn one and a half years later, not with Harrell but another fine trumpeter, Chris Rogers, who Harrell happened to have used on Time’s Mirror (to round out the trumpet motif, one of the two Brooklyn tracks is a Woody Shaw number, Theme For Maxine). These two tracks are lent some interesting color by the Danish organist Anders Rose.

My only acquaintance with Bernstein is this CD. Based on it, I’d go hear him any day of the week. Bernstein tells us (I’m Googling of course) he is ‘Marc Kibrick Bernstein,’ and Kibrick is the family name from his Jewish Eastern European — specifically Ukraine and Poland — heritage. As I write this I’m listening to a fine album I found on Bandcamp (an excellent streaming platform, by the way) called Marc Bernstein’s Kibrick 5.2: Meet The Kibricks that celebrates this heritage. I can add him to my “collection” of outstanding jazz artists with Eastern European backgrounds (Harold Danko, Larry Vuckovich, Helen Merrill, Wolfgang Muthspiel, …).

New York > Kansas City < California

What is it in this period about Tom Harrell and big bands?!

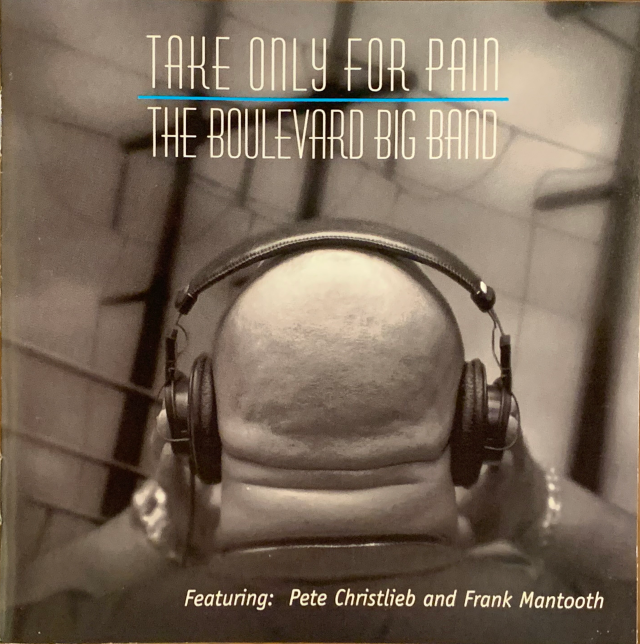

American Landscape: Led by trumpeter Michael McGraw, local musicians from landlocked Kansas City formed The Boulevard Big Band around 1985. But it was a label from California, Sea Breeze Records/See Breeze Vista, a label that apparently specialized in recording college big bands, that recorded Boulevard, and on Take Only For Pain, Boulevard’s second recording for Sea Breeze, they somehow got New Yorker Tom Harrell out to the Sound Trek Recording Studio in Kansas City, Missouri, on November 18, 1999, to play on two of the eleven tracks. We only know this from the individual track summaries in the liner notes by California Kjzz radio DJ Scott Willis — nothing else in the CD design advertises the presence of Harrell.

“You will go here on a Tuesday night. You will buy reasonably-priced beer & liquor. You will listen to incredible jazz and you will be transformed to a different age. Do not miss this place on Tuesday.” Mike Craig

“Nastiest bathroom in town. You’ll need a tetanus shot after you leave, but the beer is cheap.” Jeff Pippin

“Walking into Harling’s mens’ room is like being gassed with a hundred years of piss particles. It’s nasty in there, man — one of the city’s worst. On a bad night, it’s better to just hold it. It’s probably my favorite bar in the city.” Kansas City’s The Pitch: Where We Pee

local reviews of Harling’s Upstairs

A year or two before the studio session that produced Take Only For Pain, Boulevard became a regular Tuesday nights at the Kansas City Main Street bar & grill Harling’s Upstairs. Cheap beer, funky men’s room, great jazz. Their final recording, in 2007, was live at Harling’s (as far as I can tell, The Boulevard Big Band and Harling’s are both defunct).

Six of the eleven numbers on Take Only For Pain are standards (Old Devil Moon, The More I See You, Ladybird, Star Eyes, Superbop, Nardis) arranged by, five are originals written and arranged by, band members. In the first category, the album opener is a Latin arrangement of Old Devil Moon arranged by saxophonist Hal Melia. Solos are by trombonist Steve Dekker and Harrell on flugelhorn. In the second category, Aldente was composed and arranged by pianist Frank Mantooth, with solos by Harrell on flugelhorn again and then tenor saxophonist Bill Caldwell. Recorded in 1999, Take Only For Pain was only released in 2004, in time to be dedicated to the memory of Mantooth, who passed away in January of 2004.

Willis’s liner notes give a fine albeit discouraging account of the status of big band jazz at the turn of the century. The music on the album is also fine, especially if you have a new receiver and speakers and your own bathroom to piss in.

Two months after the Take Only For Pain studio session in Kansas City, Harrell found himself in America’s heartland again, the Dakota Bar and Grill in St. Paul, Minnesota. Mark Murphy had had an idea. That was to connect up two things he liked, Cole Porter and Latin rhythms. The result: The Latin Porter (featuring Tom Harrell). Murphy supplied the Porter; to get the Latin, he put together the brass duo of Harrell on trumpet and Al Bent on trombone (Bent also does the nicely tight arrangements), Esther Godinez on percussion (and a vocal, supplying the Spanish translation on Everything I Love), as well as Minneapolis native Peter Schimke on piano, Marc van Wageningen on bass, and Daniel Gonzalez on drums.

I have already written about Harrell and Murphy and my own evolution as a Murphy enthusiast.

Bent and Harrell in unison, Gonzalez’s percussion, Schimke’s Latin voicing, Murphy’s distinct vocal style, an enthusiastic audience: it’s all there greeting you on the opening track, I Get A Kick Out Of You. With Murphy it’s all about jazz, and we get solos from Bent, Harrell, Schimke, and Gonzalez & Godinez in an exciting drum-percussion exchange.

Harrell is splendid on this outing, including gorgeous ballad solos on In The Still Of The Night and Everything I Love.

Randy Gibbons Presents “Dear Mark and Tom,”

You are Everything I Love, so I’ve Got You Under My Skin and I Get A Kick Out Of You Dream Dancing In The Still Of The Night. I want All of You. And I dig that the Latin Porter is a bit Experimental. So here’s Looking At You. Now Get Out Of Town!

Samba-jazz

The Rio-born-and-raised, New York-transplanted (since 1975) drummer Duduka Da Fonseca* had played with Harrell on Lee Konitz’s Brazilian Serenade in 1996 and was paired with percussionist Valtinho Anastacio in the second group of musicians Harrell employed on The Art Of Rhythm in 1997. It was Harrell’s turn now to participate in Da Fonseca’s debut solo album Samba Jazz Fantasia.

Specifically, Harrell and Joe Lovano are partnered up once again on Harrell’s own Latin number Terrestris and on Jobim’s Fotografia. The Da Fonseca-Anastacio duo keeps it lively on Terrestris; Harrell’s Mel Lewis and Mike LeDonne bandmate Dennis Irwin is on bass and Dom Salvador is on piano. On Fotografia Alfredo Cardim takes over piano (and arranging), Da Fonseca’s Trio da Paz mate Nilson Matta the bass, and Duduka’s wife Maucha Adnet does some vocalizing.

Specifically, Harrell and Joe Lovano are partnered up once again on Harrell’s own Latin number Terrestris and on Jobim’s Fotografia. The Da Fonseca-Anastacio duo keeps it lively on Terrestris; Harrell’s Mel Lewis and Mike LeDonne bandmate Dennis Irwin is on bass and Dom Salvador is on piano. On Fotografia Alfredo Cardim takes over piano (and arranging), Da Fonseca’s Trio da Paz mate Nilson Matta the bass, and Duduka’s wife Maucha Adnet does some vocalizing.

Some of the Harrell-less tracks use Harrell-familiar musicians, such as Billy Drewes (see on Bobby Vince Paunetto above), David Sanchez, Eddie Gomez, Kenny Werner, and notably John Scofield and Romero Lubambo — my favorite track on the album, Lubambo’s Pro Flavio, pairs electric ‘Sco’ with acoustic Lubambo, though Pro Flavio should really be listened to back-to-back and treated as one with Da Fonseca’s Berimbau Fantasia (the berimbau, Duduka says, is his favorite percussion instrument).

My first-hearing estimation of this album was “unobjectionable,” though as often happens, its subtleties, mostly with respect to Da Fonseca’s drumming, grow on me with repeated listening. In fact I really like two numbers with Billy Drewes on soprano sax and Kenny Werner on piano: Duduka’s Coltrane-esque dedication to his late grandmother, Dona Maria — who can resist his little daughter’s voice babbling “Toca bateria, Papai” at the beginning of the track? — and, now that I focus on it, another lovely Dori Cayymi song about fishermen going out to sea, sung here by Maucha, called Saveiros (for the ones that return, each sail of their saveiro, or sloop, will have a story to tell  ). In fact, …

). In fact, …

*Da Fonseca says in the liner notes that his dream has always been to blend Brazilian music with American jazz (samba-jazz). He tells some interesting stories about growing up a Carioca, including that his mother and older brother went shopping in downtown Rio for Duduka’s birthday request for a snare drum on the day (March 31, 1964) that General Castelo Branco, who lived right across from them on Rua Nascimento Silva, overthrew the Brazilian government. The military junta was one reason Da Fonseca left Brazil in 1975.

Here we go again!: Tom’s (1) in the Midwest again, at Chicago’s Jazz Showcase (2) playing as guest artist in a big band, namely, the DePaul University Jazz Ensemble (DPUJE), directed at that time (2000) by Bob Lark. Unfortunately the CD is out of print and as far as I can tell nowhere available except in the DePaul library. Thank you to Bob Lark, though, for sending me mp3’s of the three Harrell tracks and to Katherine Dinkel at the library for taking pictures of the liner notes for me. (Under Lark, the DPUJE had an impressive history of collaborating and recording with top jazz names.)

“I feel the music of Thad Jones somehow has drifted out of many high school and university jazz programs, and this is most regrettable. Fortunately, Bob [Lark] is a Thad devotee, and three of Jones’ best are included here.”

Percussionist Steve Houghton, liner notes for the album

“I’ve had the great pleasure to visit with the DePaul University Jazz Ensemble this past February 2000. I was able to conduct a workshop, rehearse the band, and take part in a very special concert of some of my music as well as some classic orchestrations by Thad Jones and others.”

Joe Lovano, additional liner notes

Harrell is on two of the three Thad Jones classics Steve Houghton refers to in his liner notes, the two Basie-esque and quintessentially big-band numbers Little Pixie II and Tiptoe. (The third Thad Jones number on the album, sans Harrell, is To You.) A bit of discographical history: The Little Pixie is on the first recording ever made, February 7, 1966, of the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra at the Vanguard. Another live Vanguard performance in April 1967 was captured on the Blue Note recording Thad Jones & Mel Lewis Live At The Village Vanguard, where the number is listed sometimes as The Little Pixie and sometimes as Little Pixie II. The first recording of Tiptoe is, to my knowledge, on the Jones/Lewis Blue Note studio recording Consummation. As usual, I like to listen to the originals and then the versions with Harrell.

The third track with Harrell is trombonist and at that time DePaul faculty member Paul McKee’s arrangement of Harrell’s Sail Away. Needless to say, I’ve also heard the originals!

Excellent tracks, and it’s too bad I can’t hear the entire album (unless I take a trip to Chicago). Re degrees of separation: As I wrote previously, my first chance to hear live big band music was the college jazz band at the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana, led at that time by the formidable John Garvey. Harrell was born in Champaign-Urbana (they call it Urbana-Champaign now). I may have overlapped there for a year with Jim McNeely, though I never knew him. McNeely has played several times with the DPUJE.